The siberian intervention

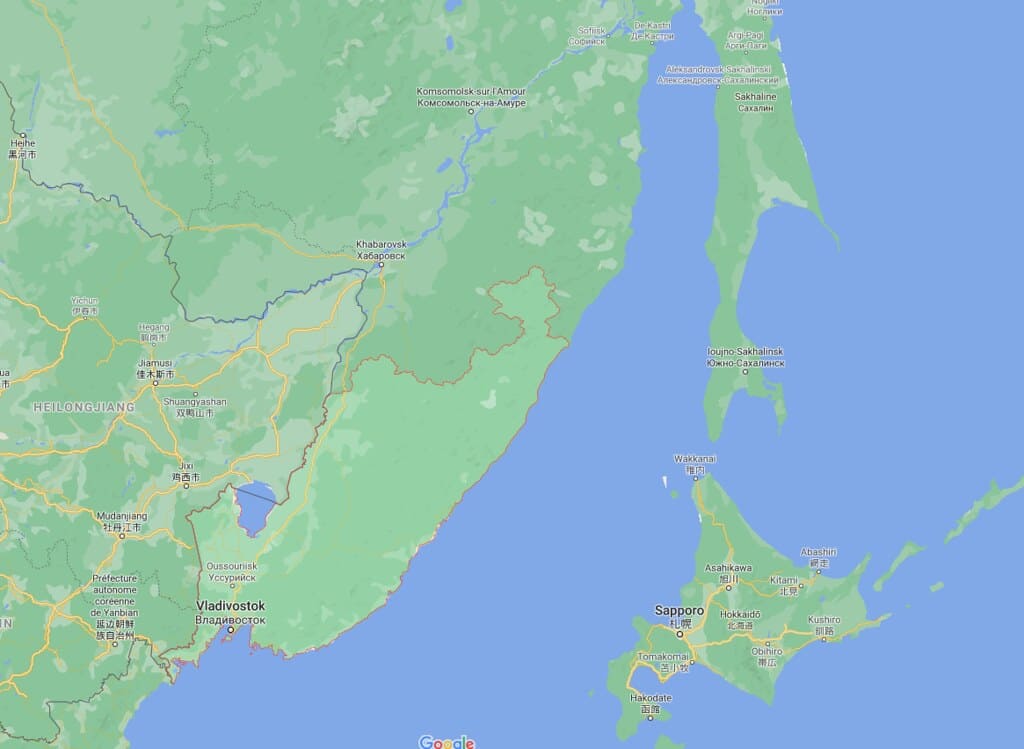

After the October 1917 revolution, the new Bolshevik government signed a separate peace with Germany. The fall of the Russian front was a huge problem for the Entente powers because it allowed Germany to transport troops and equipment from the eastern front to the western front but also required the Allies to secure their large stockpiles of accumulated material at Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and Vladivostok, and which were in danger of falling into the hands of the Bolsheviks. In addition, 50,000 members of the Czech Legion, who were fighting alongside the Allies, were now behind the enemy lines and were trying to make their way east towards Vladivostok along the Bolshevik Trans-Siberian railway.

Faced with these concerns, Great Britain and France decided to intervene militarily in the Russian civil war against the Bolshevik government. They hoped to achieve three objectives:

– To avoid the stocks of allied materials in Russia falling into the hands of Bolsheviks or Germans.

– To help the Czech Legion and bring it back to the European front.

– To resuscitate the eastern front by installing the white armies in power in Russia.

Lacking troops, the British and the French sought the help of the United States for an intervention in Northern Russia and an intervention in Siberia. In July 1918, US President Woodrow Wilson, against the advice of the War Department, authorized the sending of 5,000 troops to the US Expeditionary Force in Northern Russia (the « Polar Bear Expedition ») and 10,000 men in the US Expeditionary Force to Siberia. At the same time, the Beiyang government in China accepted the invitation of the Chinese community of Russia and sent 2,000 men in August. The Chinese later occupied autonomous Mongolia and the Republic of Tuva and sent a battalion to intervene in northern Russia as part of their anti-Bolshevik efforts.

Participants in the intervention:

– France: The troops sent by the French comprised a total of 1409 marines and Zouaves. Arrived in Vladivostok in August 1918 and after a short but hard winter campaign which earned him an army citation, the battalion was repatriated in March 1919.

– Great Britain: The British, short of troops, sent only 1,500 men to Siberia.

– Canada: The Canadian Expeditionary Force was sent to Vladivostok in August 1918. Coming from 4,192 men, the force returned to Canada between April and June 1919. During their engagement, Canadians participated in very few Of 100 men who reached Omsk to serve the administration of the 1,500 British soldiers who helped the white Russian government of Admiral Alexander Kolchak. Most of the Canadians stayed in Vladivostok, repeating routine exercises and dealing with order in the hustle and bustle of the city.

– Italy: The Corpo di Spedizione Italiano in Estremo Oriente consisted of alpine troops. It included 2,500 Italians ex-prisoners of war detained in Russia who had fought in the Austro-Hungarian army and were enlisted in the Siberian legion. The Italians played a small but important role during the intervention, fighting with the Czech Legion and other allied forces using armored trains and heavily armed to control large sections of the Siberian Railways.

– United States: The American expeditionary force in Siberia was commanded by Major-General William S. Graves and totaled 7,950 men. Although General Graves did not arrive in Siberia until September 4, 1918, 3,000 American soldiers had already landed at Vladivostok from August 15 to 21, 1918. They were quickly assigned to operations of control of segments of the railway between Vladivostok and Ussuriisk to the north. Unlike his allied counterparts, General Graves believed that the mission in Siberia was to ensure the protection of American goods and to help the Czech Legion to evacuate Russia and that this did not include fighting the Bolsheviks. Calling for conciliation on several occasions, Graves often quarreled with the commanders of the British, French and Japanese forces who wanted the Americans to take a more active part in military operations.

– Japan: The intervention of Japan was first unsuccessfully demanded by the French in 1917. However, the army’s staff later saw the fall of the Tsar as an opportunity to prevent any future threat from Russia On Japan by detaching Siberia and making it an independent buffer state. The Japanese government initially refused to undertake such an expedition, and it was not until the following year that the events led to a change in policy. In July 1918, US President Wilson asked the Japanese government to send a troop of 7,000 troops to take part in an international coalition of 25,000 men including the US Siberian expeditionary force to rescue the Czech Legion and retrieve the equipment On-site warfare. After a debate at the Diet of Japan, the government of Terauchi Masatake authorized the sending of a troop of 12,000 men, but under the single command of Japan rather than within the framework of the international coalition. Once the decision was made, the Japanese Imperial Army took control of the operation under the command of the Chief of Staff yui mitsue and began preparations for the expedition.

The Allied intervention (1918-1919):

The allied allied intervention began in August 1918. The Japanese entered the Russian territory by Vladivistok and the border with Manchuria with more than 70,000 men. The deployment of a major rescue operation was carried out by allies who were suspicious of Japanese intentions. On September 5, the Japanese met the vanguard of the Czech legion. A few days later the British, Italian and French contingents joined the Czechs in the hope of re-establishing the eastern front on the other side of the Ural and proceeding towards the west. The Japanese, with their own objectives in mind, refused to go beyond Lake Baikal. The Americans, suspicious of Japanese intentions, also remained behind to keep an eye on the Japanese. In November, the latter occupied all the ports and large cities of the Russian and Siberian cost to the east of Chita. During the summer of 1918, the Japanese Army supported white Russian elements, the 5th Infantry Division and the Manchurian-led Special Command, commanded by Grigory Semenov and supported by the Japanese, took control of Transbaikalia and founded White Government of Transbaikalia.

The Allied Withdrawal (1919-1920):

With the end of the war in Europe, the Allies decided to continue supporting the white forces of Russia and to intervene more effectively in the Russian civil war. Military support was given to White General Kolchak in Omsk while the Japanese continued to support his rivals Grigori Semenov and Ivan Kalmykov. During the summer of 1919, the white government of Siberia collapsed after the capture and execution by the Red Army of General Kolchak. On January 31, 1920, the Red Army entered Vladivostok. In June 1920, the Americans, the British and the rest of the allied coalition fell back on the city. The evacuation of the Czech legion was also authorized in the same year. The Japanese, however, decided to stay, first because of the fear of the spread of communism so close to Japan, but also of Korea and Manchuria, territories controlled by the Japanese. The latter were forced to sign the Gongota agreement to evacuate their troops peacefully from Transbaikalia. This meant the end of the regime of Grigori Semenov which collapsed in October 1920. The Japanese army provides military support to the Provisional Government of Primorie based in Vladivostok against the Moscow-backed extreme republic. The continued presence of the Japanese posed a problem in the United States, which suspected them of wanting to annex Siberia and the Russian Far East. Under intense diplomatic pressure from the Americans and the British, and in the face of rising internal public opposition due to human and economic costs, the government of Kato Tomosaburo withdrew the Japanese troops in October 1922.

The effects on Japanese policy:

Japan’s motivations during the Siberian intervention were multiple and unrelated. Officially, Japan (like the United States and other allied powers) went to Siberia to secure the war material on the spot and « rescue » the Czech legion. However, the hostility of the Japanese government towards Communism, the desire to recover the territories lost historically because of Russia, and to solve the problem of securing the northern border of Japan by creating a buffer state, Annexing new territories purely and simply were also part of the motivations. However, the intervention tore the unity of Japan, leading to opposition between the government and the army and factional struggles within the army itself. Japanese losses during the operation amounted to 5,000 deaths in combat or sickness, and expenses incurred exceeded 900 million yen.

The Czech legion:

The Czech legion is one of the main protagonists of this troubled period. Before the war, the Czechs represented the third ethnic group of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with 5.4 million subjects. Even if the majority was loyal to the Empire at the time of the declaration of war, some emigrants and inhabitants of Volhynia (a Russian region populated mainly by Czechs) asked to form an autonomous unit: druzina. This unit, which aroused the suspicion of the Russian army, continued to increase throughout the war by the addition of returned prisoners of war, in fact whole battalions and regiments changed sides during the conflict. This unit was to grow until the formation of a 50,000-strong Czechoslovak army corps in October 1917. At the signing of the peace treaty with Germany, the question of the future of these troops arose. This unit retreats towards the volga not without fighting in order not to fall in the German hands following the entry of these troops in Ukraine. This unit becomes the Czech legion. Then, on March 26, 1918, the Bolshevik government granted them a safe-conduct to rejoin Vladivostok with some of their weapons, and embark to join Europe. Only one third will succeed, the remainder being scattered all along the line of the Transsiberian. This journey will be similar to that of the expeditionary corps of the Belgian auto-guns in Russia, a veritable odyssey. Unfortunately, the objectives of the different protagonists are not the same. Indeed, if the objective of the Bolsheviks is to get rid of these cumbersome and hostile foreign troops as soon as possible under German pressure, the Westerners wanted to use them as much as possible against the Red Army troops in order to reconstitute an Eastern front with the white armies against Germany (note that these are the most strongest troops of the whole Russian army). The frictions are therefore inevitable and on May 14, 1918, a Russian soldier is killed in an altercation in Chelyabinsk, the Czech legion revolts and the city is occupied. Trotsky then gave the order to disarm the legion, which is of course impossible. The situation degenerated and the Czechs decided to join Vladivostok to embark. When the former arrived there, they saw no ship as the Western powers wanted to keep them in Russia for use against the Bolsheviks as well as against the Germans and especially to prevent them from transferring troops to the Western front. The Czechoslovak legion thus took up position on the Urals with white forces. Then they go on the offensive and several large cities fall like the city of Kazan on 7 August 1918 with the foreign exchange reserves of the Russian imperial bank. It is due to the approach of white troops of the city of Yekaterinburg that the imperial family will be assassinated in the night of July 16-17, 1918. Then the fate of the weapons turns in favor of the Bolsheviks following the resumption In hand of the Red Army by Trotsky and the defeats succeed to the defeats. The end of the war on 11 November 1918 and the announcement of the creation of the Czechoslovak state deprived them of the desire to fight in Russia and exacerbated their desire to return home. The tensions with Admiral Kolchak are only increasing, as the Czechoslovak troops are also employed in police tasks along the Trans-Siberian Railway. The advance of the Red Army continues under the disintegration of the white armies and the Czech troops then retreat to Siberia and Vladivostok where they will re-embark on 29 ships in March 1920, then they are about 67,000 people. The last legionary will leave Russia on 2 September 1920.

The situation in Vladivostok in 1918-1820:

The city concentrates at this time all the possible problems because the objectives of the different protagonists are not the same. There are the Western troops who are there to help the Russian White Army and the Czech Legion and secure the stocks of material so that they do not fall into the wrong hands. There are the Japanese who are there to use all the favorable circumstances to subtract if possible this territory from the Russian influence in an imperialist aim with at least the idea of creating a buffer state that would be favorable to them (in this case the troops White and western are a gene). There is the white Russian army which hopes to win its war against the Red Army but is divided by quarrels of personalities, finally there are the Czech troops, caught between the Russians and the Westerners. All this will lead to changes in power as events unfold. The Red Army enters Vladivostok on 31 January 1920 following victories over the White Armies (General Koltchak will be shot on 7 February 1920) and for a few months there will be cohabitation with Japanese authorities. Sergei Lazo becomes deputy chairman of the military council of the Provisional Government of the Far East, Bolshevik authority over the city. Then on the night of 4 to 5 April 1920 the Japanese army arrests Lazo and tries to take control of the city. The Japanese soldiers will re-embark later on october 22, 1922 and the city will be permanently occupied by the victorious red army on October 25, 1922.